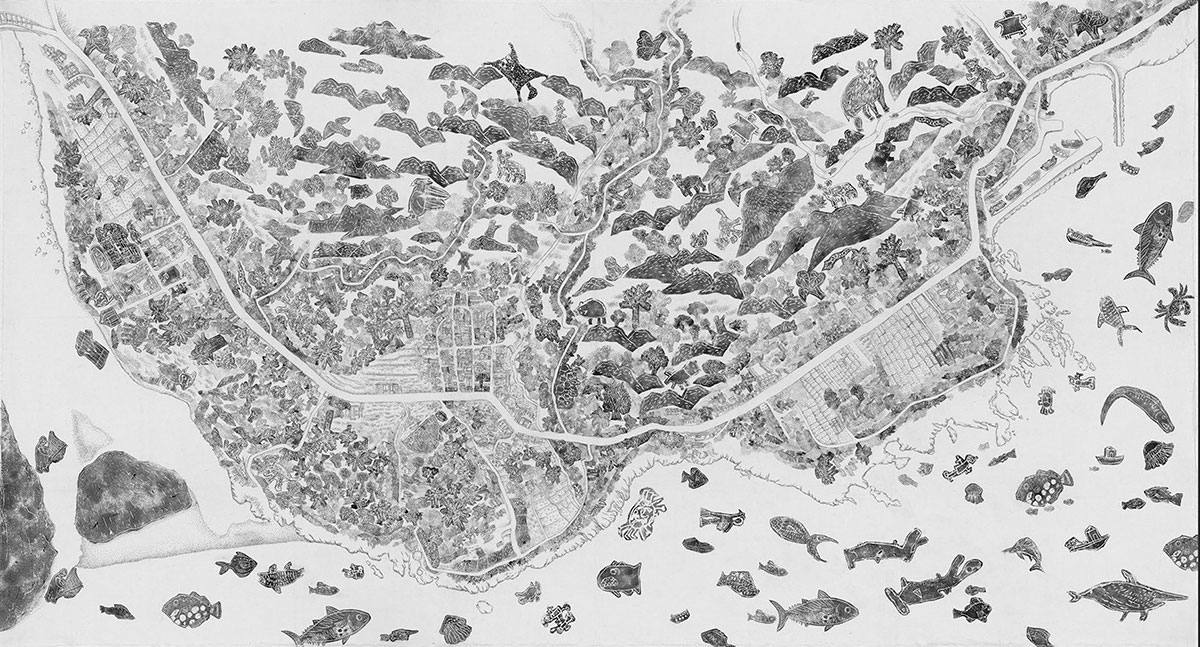

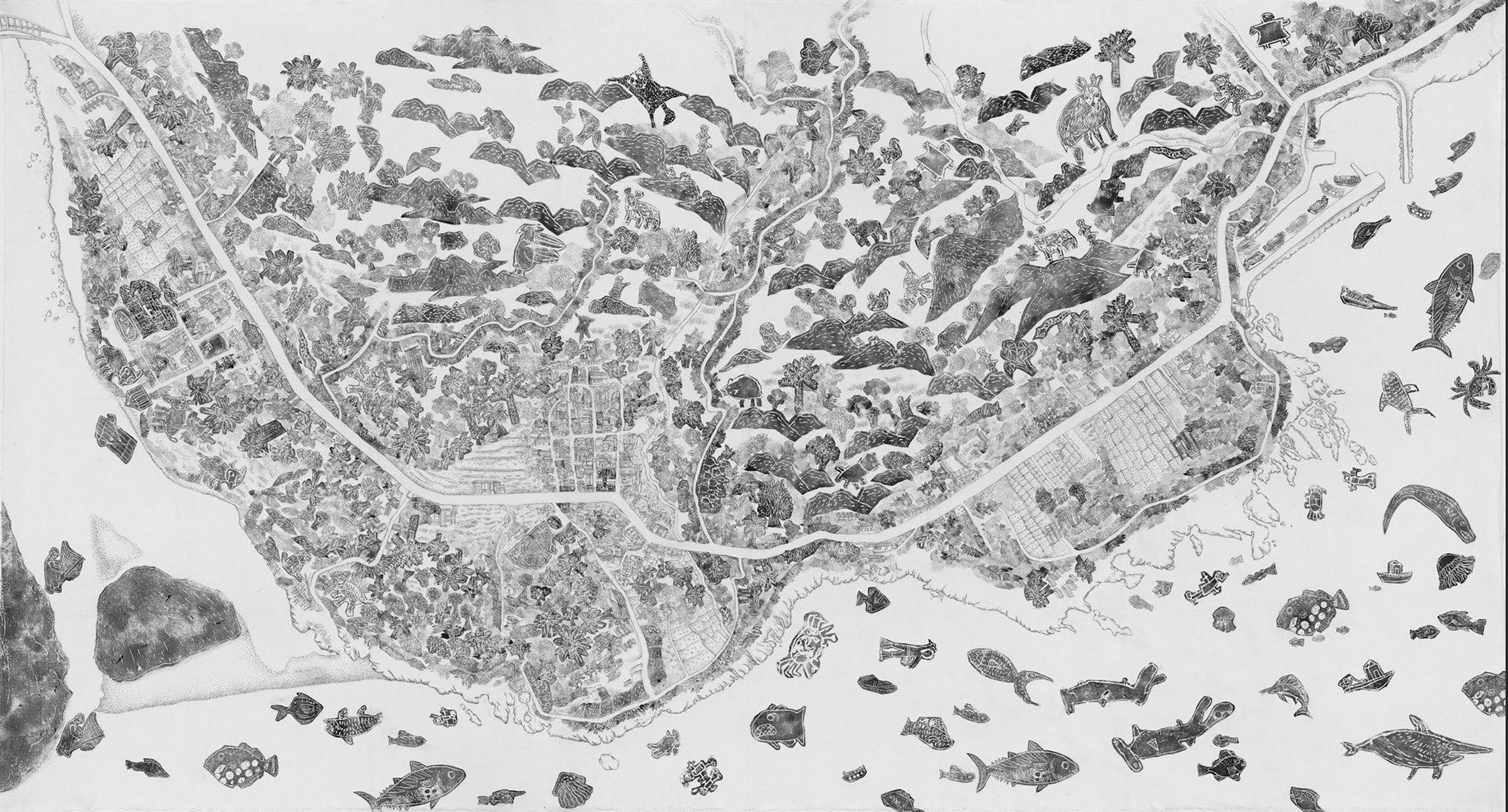

WANG Hsiu-Ju

Here We Are — Makotaay Tribe

- 2020, ink, technical pen, cotton grey fabric, 160 × 293 cm.

- Courtesy of the artist.

Curatorial Perspective

Etan Pavavalung of the indigenous Paiwan descent says that his people refer to their birthplace as “kinaizuan nua ku (tja) pudek” (the place of my/our umbilical cord). In other words, no matter where they migrate, home is where their umbilical cord was buried after birth, that eternal place of their ancestors and their source of life. WANG Hsiu-Ju’s work combines long-term field study and stationing in indigenous villages, and uses approaches of participatory art to evoke the contemporary imagination of “the presence of indigeneity.” Through her art project, Tribal Maps, which was launched in 2019, the artist has co-created spiritual and memory maps of old villages with elders from different indigenous communities in Taiwan. These elders who have lived a diasporic life recall vivid memories about their homes, from hunting, gathering, plants, rocks, to their neighbors, and with the artist, they have pieced various maps of collective memories. During this co-creative process, they return to these old indigenous villages, and retrieve their connection with their ancestors, while exploring how various factors – natural disasters, changes of survival resources, colonial governance, the mixing of modern technology with their native ecology and environment – have led to voluntary or involuntary migration of their communities. In this exhibition, the artist has remade a new, separate work based on the images co-created by the elders. In the painting series, entitled My legs are an Army of Poets, Wang delineates the relationship between spiders and landscape through the movements and postures of spiders to portray invisible webs. The imagery of intricately woven networks portrays one’s connection and relationship with the world. At the same time, the work signals the multiple networks of sentient beings, conveying how remnants of culture and tradition could be re-woven in order to search for one’s connection with the land and culture in the midst of the labyrinthine landscape of post-modernity.

Creation Description

Where is home? Etan Pavavalung, of the indigenous Paiwan tribe, says that his people refer to their birthplace as “kinaizuan nua ku (tja) pudek” (the place of my/our umbilical cord). In other words, no matter where they migrate, home is where their umbilical cord was buried after birth, that eternal place of their ancestors and their source of life. When Amis elders inquire about the place of a person’s umbilical cord, what they are really asking is where someone was born or is from. To them, home is where one’s umbilical cord has been left. It is that place that is connected to the land and the culture.

Due to politics, conflicts, natural disasters, resource shortages, and survival needs, groups have migrated, voluntarily or involuntarily, within this island. Since 2019, Wang Hsiu-Ju has been working on the Tribal Maps project with different ethnic groups and communities to apply psychological cartography to the co-creation of maps of “home.” For the Taiwan Biennial, she presents all-new independently created works based on these memory maps. Once this project is complete, reprinted maps will be sent home, to their communities.

The Paridrayan, Makazayazaya, and Kucapungane communities belong to three administrative regions of the Paiwan and Rukai tribes. The people of these communities settled in Rinari (Majia Township), Pingtung County, following the devastation brought by Typhoon Morakot. Their homes and fields are in the mountains. Their inability to return there has brought indescribable emotional pain to the elders. Wang began the Tribal Maps project in 2019 to co-create works with indigenous elders and bring them a sense of returning home through map making. Kaluluan, pateRungan, Dipit, Fakong, and Makotaay are indigenous communities in Hualien County’s Fengbin Township that are close to the mountains and the sea, where the Amis, Kavalan, and Sakizaya tribes live interdependently. The latter two migrated to this area following conflicts. In 2020, maps of these communities with products of the mountains and sea were drawn. In 2021, for the Treasure Island – Discovers the New World project, the sea route of members of the Naluwan Community, who migrated from the Meishan Community in Taitung to Xiangshan in Hsinchu in the 80s in search of a better life, was recorded. From 2021 to 2022, Wang worked with indigenous children to draw cultural maps of the Amis tribe, based on hunting, gathering of wild greens, and gathering in intertidal zones, to retrieve that umbilical cord which connects to the land and the ancestors and reveals the way home.