CHEN Chien-Pei

Ama Mama Tama

- 2021, eight-channel video, digital print, 22 min (each channel).

- Courtesy of the artist.

Curatorial Perspective

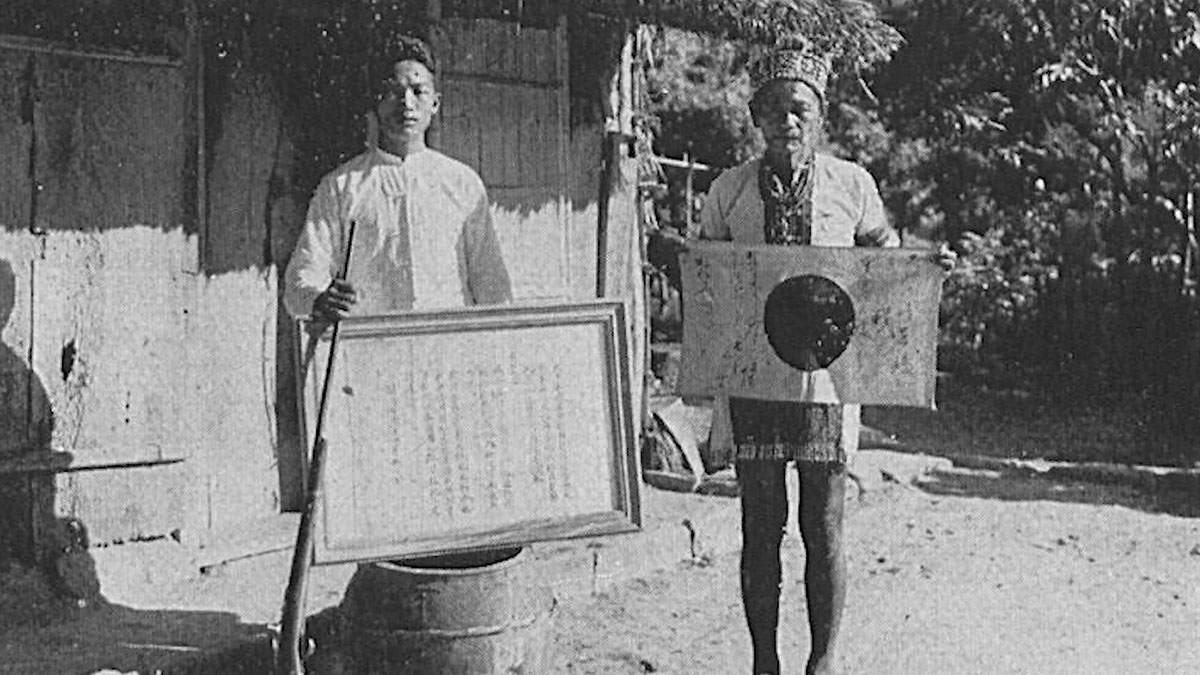

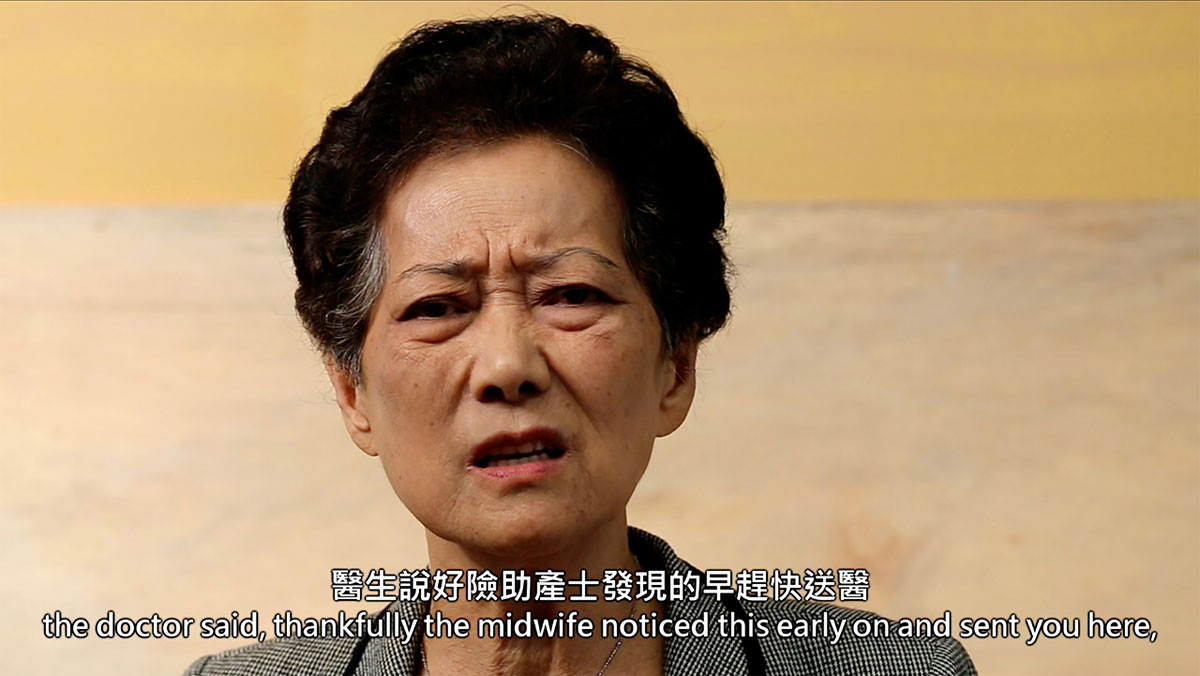

Chen Chien-Pei’s Midwife Overture and Ama Mama Tama are two installations both comprising multi-channel videos, sounds and objects. In Midwife Overture, the artist uses the interviews of Yen Kui-Ying, a professional midwife, and the women she has delivered in the past as an introduction to delineate women’s situations in our society, and the meaning of human procreation. Socrates once compares his role to a philosophical midwife—he does not tell people what the truth is, but rather helps them obtain the truth that is already within them. Naturally, the role of a midwife speaks about human procreation, the continuation of the life of all species, as well as how this thread of sentiments has kept intertwining and entangling. Shown as an eight-channel video installation, Ama Mama Tama revolves around four coastal Pangcah communities, namely, Kaluluwan, Paterungan, Fakong, and Makotaay, and comprises interviews of thirty-two interviewees of different ages and indigenous descent, including the Sakizaya, the Bunun, the Amis, and the Kavalan tribes. The artist conducts a long-term field study, and records the individual and inter-generational life histories in these communities, allowing their video recordings to be natural presentations of distinct generational backgrounds and the flow of time and space. The interviewees ranged in age from 20 to 90. The memories of fathers shared by people in eight age groups moved the time frame of this work to the 19th century, more than 100 years ago. At the end of the video are historical images of colonial persecution, such as of that of the indigenous peoples of Central and South America by the Spaniards, that of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan by the Japanese and after the arrival of the Kuomintang government, and the fight for equality in South Africa. Both works use the body as a starting point, and explore the colonial experiences of different periods from the perspective of individual life stories, inquiring into fragmentized individual lives constituting the human condition in different eras, while demonstrating how biopolitics is merged with indigenous collective memory and history.

Creation Description

For thousands of years, bearing children to continue the family line has been considered the responsibility of wives and daughters-in-law. Chen Chien-Pei once heard ”Mama” from China describe her pain of miscarrying a male child. (If he had lived, he would have been his older brother.) In addition, Chen’s grandmother in Nangang talked about how she missed her children who had died prematurely. The pressure once placed on women to give birth seems incomprehensible to modern people. Over a 60-year period, from the Qing dynasty, the Japanese colonial (1895-1945), till Taiwan’s retrocession, there was no advanced medicine and each time a woman gave birth life hung in the balance. Due to their direct involvement in this, Chen became fascinated by midwives. In Midwife Overture, he attempts to outline the circumstances of women and their apprehension about bearing children. Part of a traditional dowry, a birthing chair, and the service area of midwife Yan Gui-Ying serve as metaphors for the changing times. Through the eight-channel projection of moving images onto backgrounds of different colors and interviews with Yan and two mothers whose babies she delivered, childbirth taboos in Taiwan, experiences of delivering babies, offspring and inheritance, and the status of women are explored. Also included is a collection of heartfelt descriptions of pregnancy and childbirth, inspiring reflections on the estrangements of modern people.